Parallel imports: navigating the grey market

Where there is trade, trade mark infringement often follows.

For brand owners, in particular in the pharmaceutical field, one of the most difficult trade arenas to navigate can be the grey market.

Our guide to the grey market, what it is and when brand owners can stop grey market goods is below.

The grey market

Just as grey sits between black and white, the grey market sits between the black market, where goods are sold illegally (e.g. counterfeits or illicit drugs) and the white market, where goods are sold legally, with the approval of the manufacturer.

Grey market goods (sometimes referred to as parallel imports) are genuine, non-counterfeit goods of a trade mark owner, like white market goods. Yet, after first being put on the market, the goods are imported into an economic area and sold there without the consent of the trade mark owner. This is what makes them grey market goods. They are genuine in the sense that they were manufactured by the owner of the trade mark but unauthorised for sale in a specific jurisdiction.

The law in relation to grey market goods can sometimes be a grey area. Litigation and case law at the European and national levels set out when grey market goods will infringe the rights of the trade mark owner and when they will be permitted. This is an issue that comes up with particular frequency for industries which have specific packaging requirements for different countries, such as pharmaceuticals.

Stopping grey market goods

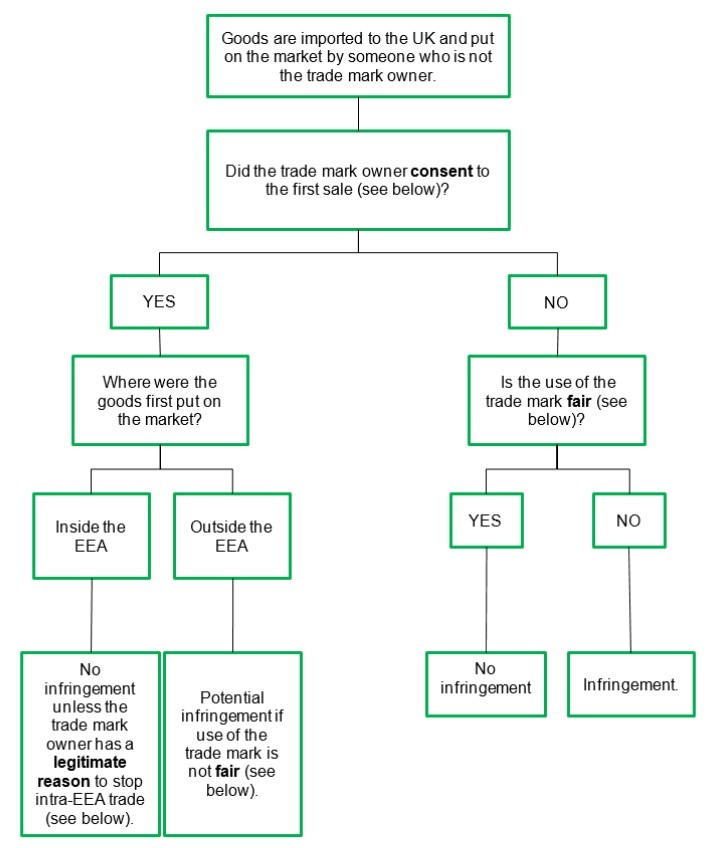

If grey market goods infringe trade mark rights, they can be stopped. In the assessment of infringement the relevant factors for trade mark infringement are:

- whether the trade mark owner gave consent for the first sale of the goods;

- where the goods of the trade mark owner were put on the market; and

- whether the importer’s use of the trade mark is fair, namely in a descriptive way or to make a fair comparison.

These three issues come into play in different scenarios, the outcomes of which are set out in our “grey mart chart” below.

The Grey Mart Chart

Consent: Consent of the trade mark owner can be express or implied. Express consent includes selling the goods to a wholesaler or retailer. The threshold to imply consent is high. It requires the trade mark owner to have unequivocally renounced its rights[1]. Nevertheless, to imply consent is not impossible and can be done when consent is obvious[2].

Fair use: There is a defence to infringement if a trade mark is used descriptively, in accordance with honest practices in industrial and commercial matters[3]. This will not apply if the use of the trade mark implies there’s an authorised connection between the brand owner and importer or if it takes advantage of or is detrimental to its reputation or distinctive character.

An advertisement referring to a trade mark to compare the goods of the brand owner and importer can also be permitted but only if this is an honest comparison of the trade mark owner and importer’s goods[4].

Legitimate

reason to

stop trade: Usually, if goods are put on the market in the EEA, with the brand owner’s consent, then the brand owner’s rights are “exhausted”. The brand owner can control the first sale, but not resales. However, there is an exception to this if there is a legitimate reason to stop trade. This could be if the condition of the goods has been changed or impaired, for instance they are repackaged. However, under certain circumstances, even repackaging may not be enough to enable a brand owner to stop resales (this issue is particularly common for pharmaceutical products)[5].

The above is the position for goods imported into the UK (as of today). However, it is important to note that different rules apply when goods are exported into other territories. Those rules depend on the laws in the countries into which goods are exported and they do not always mirror the UK position.

For example, under UK law, imports of goods from the EEA, into the UK, are not restricted by trade mark law. Goods with a trade mark on them, first put on the market in the EEA, then imported into the UK do not infringe UK trade mark rights, so long as there is no legitimate reason to stop trade. However, goods bearing a trade mark, first put on the market in the UK, then exported into the EEA may infringe EU trade mark rights. Businesses exporting from the UK to the EEA may need to seek permission to export goods legitimately.

Grey market enforcement strategy

For brand owners, grey market goods can lead to a loss of control over product quality. Where grey market goods could affect consumer or (for pharmaceuticals) patient safety, brand owners can take a stronger position.

However, there are plenty of potential stumbling blocks along the way. From the start, it is vital that a clear strategic plan is in place, to make sure infringing grey market goods can be stopped.

[1] Zino Davidoff SA v A & G Imports Ltd; Levi Strauss & Co v Tesco Stores Ltd; Levi Strauss & Co v Costco Wholesale UK Ltd, Joined cases C-414/99 to C-416/99

[2] Mastercigars Direct Ltd v Hunters & Frankau Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 176.

[3] S 11(2)(b) UK Trade Marks Act 1994 (TMA 1994)

[4]Trade Marks Act 1994, s 11(2)(b). There are also specific laws on comparative advertisements.

[5] Bristol-Myers Squibb v Paranova A/S, Cases C-427/93, C-429/93 and C-436/93, [1996] ECR I-3457, [1997] 1 CMLR 1151, [1997] FSR 102; Boehringer Ingelheim and others C-348/04 and C-143/00; Junek Europ-Vertrieb GmbH v Lohmann & Rauscher International GmbH & Co. KG C-642/16