About the authors:

Chris Mason is a senior associate patent attorney at Appleyard Lees IP LLP. Chris works with his clients to ensure that their innovation is captured, turned into valuable assets and their commercial interests protected. Day-to-day Chris handles cases in fields including industrial chemistry, pharmaceuticals and healthcare, involving technologies such as new synthetic polymers, catalysts and active pharmaceutical ingredients.

Ashley Wragg is a European patent attorney. Graduating with a first class master’s degree in chemistry from the University of Sheffield, Ashley then completed a PhD in chemistry between the University of Sheffield and the A*STAR institute in Singapore. Ashley has particular expertise in the areas of polymers, plastics, packaging and catalysis.

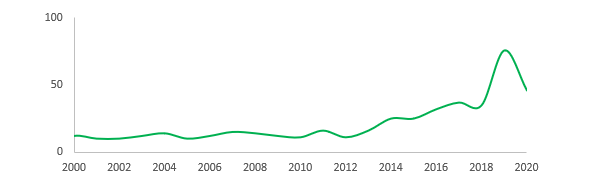

Figure 1 – New global patent filings per year (2020 data not yet complete)

Innovation in the plant-based meat sector is aiming to help to solve some of the problems associated with animal-meat production. Unsurprisingly, companies operating in this sector are protecting their Intellectual Property (IP) position through the development of patent portfolios. While annual global patent filing numbers toward plant-based meat substitutes maintained a consistently low level from 2000 until 2013, since 2013 the number of annual patent filings has significantly increased year-on-year, and in the last couple of years the filing numbers have been reaching four-times the level of 2013.

The increase in annual patent filings goes hand-in-hand with a growing awareness of the sector. Consumers are increasingly embracing social causes, and they are seeking products and brands that align with their values. Studies suggest that more than half of consumers are willing to change their purchasing habits to help reduce negative environmental impact. There is also mounting pressure from advisory groups, for example, a government-commissioned review recently recommended that meat consumption is cut by 30% within a decade.

Market leaders and patent landscape

Recently companies such as “Impossible Foods” and “Beyond Meat” have become market leaders in the plant-based meat sector with plant-based burgers that are said to closely imitate animal-based meat. These plant-based meat analogues are marketed as allowing customers to reduce their environmental impact without having to give up their favourite foods.

Figure 2 – Impossible Burger

Impossible Foods and Beyond Meat, as well as Gold and Green Foods, are also the leading the way in terms of the number of patent filings for new ‘meat alternative’ focused companies. In terms of longer established companies, Nestle stands out as a high patent filer for various ‘meat analogue’-related innovations. More generally speaking, the patent applications filed in this sector are spread quite thinly across a large number of different applicants.

The US and Europe are ahead as the territories from which the most patent applications have originated. In recent years, the number of new patent applications originating from China has increased significantly, although these applications follow the trend found in other sectors, with almost none of these patent applications being extended outside of China. This contrasts with the patent applications originating in the US and Europe, the majority of which are developed into international patent families. It is likely that many of the China-originating filings were driven by state-offered monetary incentives.

The patent filings reflect the years of research and development, and multiple different innovations, that it has taken to arrive at the current imitation plant-based meats that are available on the market.

Focus – Impossible Foods Inc

Impossible Foods Inc first made headlines in 2016 for its meatless burgers that would “bleed” like real meat. ImpossibleTM Burger includes over 21 ingredients including soy as its main protein sauce, coconut and sunflower oils to provide fats to make their burgers juicy, and a wide range of plant-based additives to arrive at the end product. Arguably, the most important part of their recipe is the not-so-secret “secret ingredient” – use of their “Heme”.

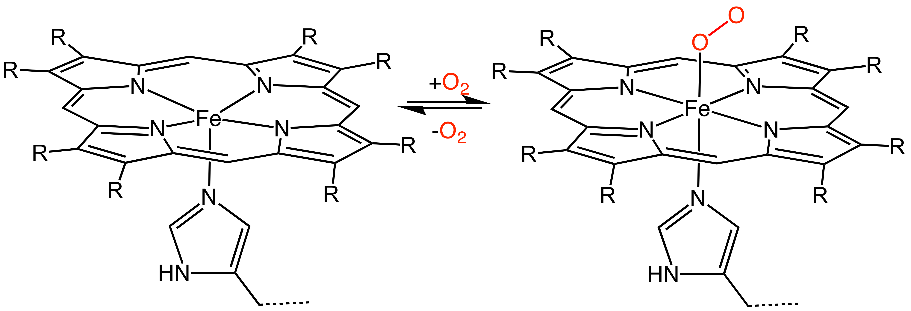

Heme (or Haem) is a coordination complex of iron in a porphyrin. Heme is precursive to haemoglobin and it binds to oxygen to be transported around your body in your blood. Meat is mostly muscle tissue which contains high concentrations of myoglobin. Myoglobin is a distant relative of haemoglobin and similarly transports oxygen and stores oxygen in the muscle using the same heme unit.

Impossible Foods identified that heme is the flavouring in meat that “makes meat taste, well, meaty”. And it is not only the flavour. Upon cooking heme is involved in producing many of the aromas that we associate with cooked meats.

Figure 3 – Heme

Impossible Foods identified that heme is the flavouring in meat that “makes meat taste, well, meaty”. And it is not only the flavour. Upon cooking heme is involved in producing many of the aromas that we associate with cooked meats.

To solve the problem of how to make a meat-free product taste like meat, Impossible Foods had found at least part of the solution in heme.

Nevertheless, problems remained, not least finding a way to obtain heme from a non-animal source on an industrial scale.

Originally, Impossible Foods extracted heme from naturally occurring leghemoglobin that is found in the roots of soybean plants. However, this source would not be suitable for large scale up. For plant-based food to meet the likely world demand, huge quantities of it are required. Further innovation was needed, and Impossible Foods turned to GMOs (genetically modified organisms). Yeast was genetically engineered so that it could produce the same leghemoglobin as found in the soybean roots. This led to yeast that when fermented would produce large quantities of heme.

Although not yet available in the EU or the UK due to strict rules and regulation on genetically modified materials, the market for plant-based meats is primed. The popularity of the ImpossibleTM Burger in the US indicates that if/when it is approved for use in the EU/UK it may be in demand.

It comes as no surprise that companies such as Impossible Foods are protecting their intellectual property in this field. Impossible Foods Inc are linked with at least 15 Patent Families with a total of 242 applications, 97 of which are currently granted. These patent filings protect their innovations not only in relation to the foodstuffs themselves, but also in supporting fields such as methods of preparing proteins, new reagents and GMOs.

The earliest patent application associated with Impossible Foods Inc aimed to broadly protect the meat product with claims to “A meat replica” which comprises an “iron carrying protein”. Subsequent patent applications included EP2943072 which is related to a “food product comprising a) a highly conjugated heterocyclic ring complexes to iron ion; and (b) one or more flavour precursor molecules …”.

There were also early applications capturing innovation around the preparation of the proteins used in their meat analogues, such as US10093913, which relates to a method for purifying a soybean 7S protein. Further applications related more specifically to innovations within these processes, such as US9737875, which relates to a new affinity reagent for protein purification. These affinity reagents are used to purify protein from crude solutions i.e. in the process of preparing proteins for use as food ingredients, such as the leghemoglobin.

US10689656 is an example where Impossible Foods have captured innovative genetically modified yeast cells and methods of genetically engineering methylotrophic yeast.

Importantly, many of the steps that led to Impossible Foods being able to provide a commercially viable source of non-animal heme are patentable, and Impossible Foods have duly protected their innovations to provide a strong base from which to expand their meat free vision.

Looking to the future

As the demand for plant-based meats is continues to increase, and innovation continues to provide new solutions to problems along the road to commercialisation, we expect to see increasing year-on-year filing numbers. Research continues at pace to try and address on-going problems such as matching texture, colour, flavour, and taste profiles of the animal-based meats, as well as hitting economical cost points. The market also continues to explore new solutions, with pea coming to the fore as an alternative to soy.

We can expect to see patent applications directed toward plant-based meats that are better at mimicking not only the taste and aroma of meat but other features as well. Similar to how Impossible Foods innovated by providing a burger that bled. We may see patents directed toward, for example, plant-based tendons and collagen (and the processes for making them), to perfect a chewy analogue steak. Food textures are very important to provide a convincing end product. It may be there will be patent applications towards new matrixes, for example, that provide a foodstuff with the “flakey” texture of a fish.

An example of such innovation is the Spanish based start-up NovaMeat. NovaMeat claims to have developed the world’s first 3D-printed plant-based beef steak with the texture of a cut of beef. In EP3833194A1, NovaMeat Tech S L applied to protect their process for the manufacturing of an edible microextruded product containing more at least 2 layers of viscoelastic elements that contain protein, an edible psudeoplastic solvent polymer and solvent. They also have applied to protect the edible microextruded product obtainable by their process. NovaMeat technology aims to mimic meat starting with beef, salmon and pork.

As is often the case with high technology fields such as this one, producing a technically acceptable product is only a part of the battle. The product must be consistently producible at large scale and at a competitive price point. As such, we can expect to see patent applications directed toward solving scale-up and cost problems as the industry continues to develop.

For any advice or information regarding protecting your innovations, please contact our life science experts at Appleyard Lees.