About the Author

Bill Lister is a partner and IP Solicitor at Appleyard Lees IP LLP. Bill has a wide range of experience advising UK, US, European and global clients, with a substantial reputation spanning branding issues, registered and unregistered trade marks, copyright, design, patents and trade secrets. Bill advises a number of global household names, in conjunction with public and private companies, and public sector organisations.

As Summer winds down into Autumn, Christmas cannot be far behind. Inevitably, kids’ thoughts soon will turn to what they’d like to find in their stockings.

Toys for the very young do not need to concern themselves too much with realism. However, older children today are used to the very realistic images in the video games they play and the high-definition television programmes they watch.

For generations, children have loved playing with and collecting toy cars – the more realistic, the better. To be a recognisable reproduction of a full-size original car, a toy car should be a replica of an actual car, including the car manufacturer’s official branding and badging. However, these scaled-down reproductions can infringe both design and trade mark rights in certain circumstances.

Many car manufacturers, especially at the higher end of the market (Mercedes, for example), produce their own replica toy cars that are labelled with the scaled-down badging of the original. In these cases, no problem arises because the manufacturer, or an associated company, owns or is licensed to use the relevant trade mark rights. The use of the actual badge is likely to drive up the prices of the replica cars, due to the inevitable licensing costs.

The problem arises where third-party toy manufacturers wish to produce not merely toy cars, but replica cars, which, without the badging, could not be said to be truly replicas – it is the badging which makers them true replicas.

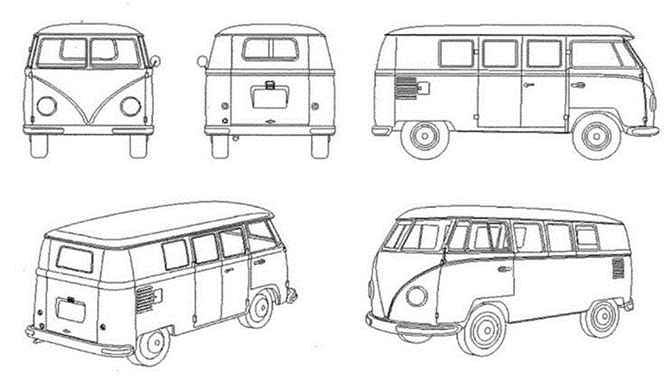

A good example is the German toy company Schuco who, since 1912, have produced “European Classics”. Below is an early image of the widely loved Schuco replica Volkswagen T1 Campervan, replete with the iconic, distinctive, and well-known third-party drinks trade mark, “Martini”:

Clearly, prohibiting the manufacture of replica toy cars for children to enjoy and collectors to collect, has an anti-competitive effect on the toy market as it gives automobile manufacturers the exclusive right to produce replica toys, and to charge a premium price. It is certainly open to them to grant licences to toy manufacturers to reproduce the replicas and the badges, but the cost to the manufacturers in royalty payments is likely to be such as to be reflected in the retail price driving up prices and potentially distorting the market.

Car manufacturers can protect the overall appearance of their vehicle and the badging upon it, in various ways, including 3D trade marks.

Both E.U. and U.K. law require a trade mark (amongst other things) to be “distinctive”, that is, capable of guaranteeing to the average consumer the identity of the source of the product. The “average consumer”, a legal construct, is a notional individual who knows the market well, but not an expert, who has an eye for detail, but not a perfect total-recall memory.

In a relatively recent case decided at the First Board of Appeal of the European Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO), the Board examined whether Volkswagen’s 3D trade mark application for the shape of the iconic VW campervan, more popularly known as the “Bulli”, was a valid trade mark. If yes, this could prohibit the manufacture, on any scale, of any vehicle, real or toy, shaped like the “Bulli”. The trade mark was, in essence, a series of five line-drawings of the “Bulli”, rotated through 180°:

In its judgment handed down on 29 November 2021, the Board ruled that it was, indeed, a valid 3D trade mark and capable of registration as such. The Board held that vehicle shapes could be distinctive in their respective markets, remain in customers or average consumers’ memory, and therefore identify the manufacturer as the originator of the design. This accords with an earlier German case regarding a trade mark in the shape of the Porsche “Boxster” (German Supreme Court (BGH), decision of 15 December 2005, I ZB 33/04).

In giving its judgment, the Board set out a three-point general test of distinctiveness:

- In cases such as this, distinctiveness will be difficult to prove as the average consumer is not used to inferring the origin of a product simply from its shape without any further indication, such as badging.

- The more closely the 3D trade mark resembles the product it is intended to represent, the higher the hurdle for proving distinctiveness.

- For such a trade mark to have distinctive character, it must not be of such a type as to diverge from those common in the market, in order that the average consumer can identify the trade mark as fulfilling an essential trade mark function, that is, as an indicator of its source and differentiate the product from those of other manufacturers.

The Board was driven to this decision by the “Bulli’s” unique and distinctive V-shape on the front of the campervan, positioned where the average consumer would expect to find, on most cars, a grill and brand logo. Also, the overall shape and configuration of the campervan was different to anything else on the market, especially when the campervan was first introduced in the 1950s. The shape of the “Bulli” was therefore distinctive on its own, even without the application of VW branding.

At this point, for completeness, it is worth briefly looking at the decision of the General Court of the European Union (GCEU) dated 24 October 2019 regarding the famous “Rubik’s Cube” as this case concerned an actual toy, although not a scaled-down reproduction of a real-life product.

The image concerned was a representation of the actual product rather than a scaled-down version:

Applying the provision of the then E.U. Trade Mark Regulations, which disqualified from registration “signs which consist exclusively of the shape, or another characteristic, of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result” [my emphasis], the GCEU cancelled the registration. In this case, distinctiveness was not a live issue. Perhaps this is not surprising as the trade mark depicted the operative features of the game.

A similar approach was taken on appeal by the European Court of Justice in 2010 regarding the instantly recognisable Lego brick (ECJ) in Lego Juris v OHIM, albeit stating that the shape of the Lego brick fulfilled a particular function – that is, to fit each other to create a larger shape – in respect of which Lego should not have a monopoly.

So, if that is the position in the E.U., what is the position in the U.K. after Brexit?

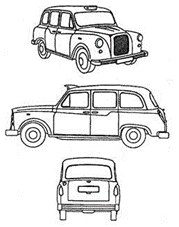

At first glance, the position taken in the “Bulli” case does not appear consistent with that taken by the High Court in England. In 2016, Mr. Justice Arnold (later Lord Justice Arnold) considered the trade mark for the (some might say or expect) equally iconic London Taxi (London Taxi Corporation Limited trading as the London Taxi Company v (1) Frazer-Nash Research Limited and (2) Ecotive Limited [2016] EWHC 52), which was considered primarily on the issue of distinctiveness:

The judge ruled that as so-called “black cabs” are usually purchased by taxi drivers (in this case, the notional average consumer) and not by general members of the public, then the trade mark was not generally distinctive. However, this is slightly different to the position in the “Bulli” case where the market was the campervan-buying public in general, to which the average consumer belonged.

In a more recent case, the U.K. position seems to have solidified behind Mr. Justice Arnold.

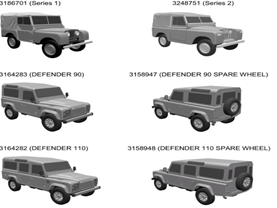

On 3 August 2020, the High Court heard an appeal from the U.K. Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) regarding an application by Jaguar Land Rover Ltd. for the 3D shapes of several vehicles, but by way of example, the Land Rover Defender:

In reaching its decision, the UKIPO applied the three-point test used in the “Bulli” case, concluding that the 3D shape did not constitute a “significant departure from the norms or customs of the sector”. The High Court upheld the UKIPO decision on the basis that it was not entitled to substitute its own opinion for that of the UKIPO, whose decision contained no material error of law and was not otherwise manifestly wrong.

This is problematic because, since the U.K. withdrew from the E.U. on 1 January 2021, decisions of E.U. courts do not bind the U.K. High Court. How persuasive the U.K. courts will find decisions of the E.U. courts is yet to be seen.

Let’s get back to toys.

The European Court of Justice (ECJ) considered trade mark infringement (rather than validity) in Adam Opel AG v Autec AG (Case C-48/05) [2007] ETMR 33, handed down on 25 January 2007. Autec manufactured scale-model toy cars, including a model of Opel’s Astra V8 coupe. Being a detailed and accurate replica of the original, it incorporated Opel’s ‘Blitz’ logo (a flash of lightning overlapping a circle) on the radiator grille:

Opel had the trade mark registered in Germany in respect of ‘motor vehicles’ and ‘toys’ and objected to its use by Autec. The ECJ held that the logo was not used on the toy as an indication of the origin, kind, or quality of the goods. Instead, it was merely an element in the accurate scale-model reproduction of the original car. The point of the toy was that it had to be recognisably an Opel model.

When referred back to the German court by the ECJ to apply the facts of the case in question, the German court ruled that the average consumer would expect a scale-model car to include the badge of the original on its grill, and therefore use of the badge did not indicate that the model originated with the original, full-size car manufacturer. The packaging of the scale model would have depicted Autec’s own branding and, in common with most or all such toys, the name of the originator would have appeared in the casting of the baseplate of the scale model.

The thinking behind the judgment was clear. If the average consumer did not regard Autec AG’s use of the “Blitz” trade mark as an indication of the origin of the scale model, then there was no infringement.

To sum up, in the U.K. there will be no infringement where the average consumer does not believe goods come from the owner of an economically linked undertaking or business. If the 3D trade mark is not distinctive, the mark will not be valid. The application to the toy of a small-scale version of the manufacturer’s mark (for instance, the “Blitz”) will not be regarded by the average consumer as an indicator of the origin of the toy but will be merely understood as an ingredient of the replica model.

Is there anything toy manufacturers can do to give added protection?

I would suggest that all packaging should be very clearly marked with the toy manufacturer’s branding and relevant trade marks and, ideally, the packaging should state somewhere that this is not a licensed product. This information should also be cast in the baseplate (or elsewhere as appropriate) on the toy itself.

Bill Lister

View bio